But why does anyone film anything? To remember it and, in the case of home viewing, to watch it repeatedly, allowing the images to spread across time like a curse.

The same week I began writing this piece, the entertainment company A24 Films texted me to advertise a unique contest, as if they sensed my summons. If I replied with a vintage TV emoji, the text promised, I could “return to the midnight realm” and be entered to win a “playable VHS” of Jane Schoenbrun’s 2024 film I Saw the TV Glow. What particularly piqued my interest in the A24 advert, aside from its timing—which I’ve chosen not to consider too closely—was the phrasing “playable VHS.” That this prize copy of Schoenbrun’s film would be playable implies that other VHS tapes are not, in which case, what’s the point? Even if the VHS were playable, how would I play it if I were not one of the Analog Girlies™ who happened to have a restored VHS player rescued from the bowels of eBay?

A quick peek at the A24 Store, where said playable VHS retails for $30, provides some critical insight for those willing to read beyond the blurry static lines. The product blurb describes the tape as a “limited edition playable VHS transfer of Jane Schoenbrun’s generational horror film, presented in letterbox format.” The film underwent many modifications to acquire its vintage-style packaging. By migrating the format from film to VHS, A24 enacts another form of transfer, a kind of reverse-digitization that propels the images into the past. In short, A24’s specification that the VHS is playable promises a certain kind of time travel that the actual viewing experience belies. Within the film’s plot itself, the VHS’s mystical occultism enables the characters to escape the present and, whether willingly or not, access another dimension; and yet, this dimension is not a liberatory space but a horrifying one as Owen and Maddy do not belong there. Just like the manipulation required to transfer episodes of The Pink Opaque to VHS results in Maddy and Owen’s nefarious capture by the medium, A24 transfers I Saw the TV Glow to a now extinct technology thus reinforcing rather than obfuscating the fact that this film does not belong on VHS, playable or otherwise, and that the VHS was not meant for modern eyes.

This necessary modifier of “playable” amplifies the material anxieties of storing time in a box, where the object that houses memory is corporeal and physical yet its contents remain inaccessible. In this way, the VHS tape indexes a particular crisis point at the intersection of memory and technology, a crisis point that has been taken up by several contemporary horror and dark comedy films (in addition to I Saw the TV Glow, one might think of Zach Cregger’s Barbarian or Dave McCary’s Brigsby Bear). The meeting of technological obsolescence with a fundamentally human cognitive process rears its head in this specific moment because of a rapidly passing mechanical singularity. Thanks to the availability of more affordable recording and home viewing devices in the mid- to late-1980s, millennials were the first generation to have their childhoods recorded on film. This phenomenon was not, however, equitably distributed; the home-recording boom was largely a white, middle class, suburban experience, a caveat which itself speaks to the deeper anxieties underlying techno-obsolescence. Early VHS ads emphasized the technology’s ability to freeze and trap time. Kodak, for instance, introduced its T-120 with the tagline “When the moment means more. Tape it. And keep it.” Home movies promised infinite replayability, a tenuous circumvention of memory’s failings. And yet, any VHS could be reused, precious memories irrecoverably taped over, just as the tape degrades through time when exposed to heat and moisture. The VHS houses the past within fragile plastic casings, a replayale past that can be erased with the press of a button.

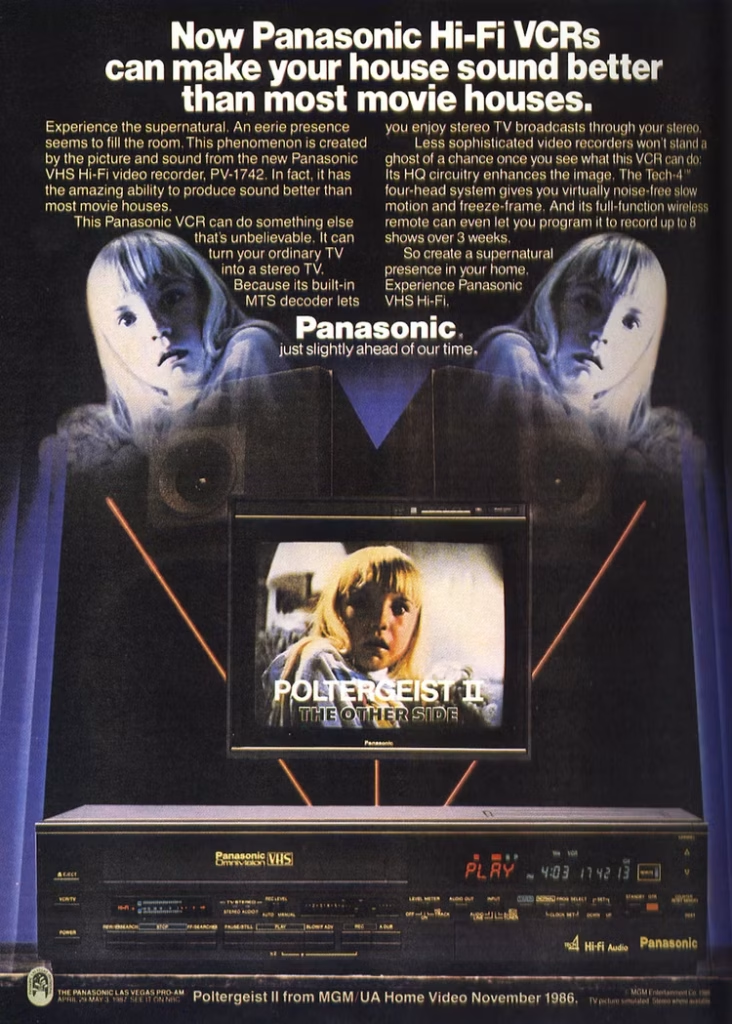

The VHS suspends the past within a mercurial and unstable physical format, much like a ghost in the machine. Telecommunications and the occult share a long prehistory—Alexander Graham Bell purportedly invented the telephone in the hopes it would allow him to speak with his dead brother. The VHS imbues this history with a late twentieth century bent. At once stubbornly tangible in its apparatus and ephemeral in its content, the VHS has acquired (oc)cult status, both with archivers who treasure the objects themselves and with cinephiles who surreptitiously traded tapes to resuscitate box office flops into cult classics. Even before the demise of the VHS, the alignments between home viewing and the paranormal became apparent. In 1986, Panasonic partnered with MGM to use Poltergeist II in its VCR ad, which begins, “Experience the supernatural. An eerie presence seems to fill the room” and invites consumers to “create a supernatural presence in your home.” Home viewing and recording struck an insidious bargain: imbue the technology with the fundamental narratives of ourselves and our historical moment and, in return, we could endlessly rewind the tape. And yet, our access to these narratives is increasingly jammed with static. Not only do the tapes degrade, but the device that provides this access is now obsolete. The VHS player provides us with a structure and a warning for thinking through millennial self-construction. A generation that grew up having their daily lives recorded for posterity might now find themselves alienated from their past selves because the objects that they thought would remember it for them are now obsolete or corroded. This phenomenon for self-techno-preservation has reached its tentacles beyond millennials, as trends like RETROSPEKT welcomes users “to our time machine” by reviving and reselling retro technology.

What keeps nagging me, as a 90s kid for whom techno-obsolescence has become a routine event, is how the once-shiny promise of VHS has not only dimmed, but thrown all of us whose memories live on unviewable black plastic bricks into a generational identity crisis. We are, to reconfigure Marshall McLuhan’s phrasing, no longer the medium of our own message, and the medium that holds the message no longer bears a teleological relationship to us at all. The VHS no longer serves its direct function as a memory storage device. Millennials rush to transfer their childhoods to a more stable digital format, aided by services like the appropriately named Mystic Media. “VHS cassettes aren’t just obsolete,” Mystic derides, “physically they aren’t good stewards of your home movies.” If our technologically degrading memories are ghosts, then the VHS is a bad haunted house, a corroding medium (format) that fails as a medium (psychic link to the dead).

I Saw the TV Glow joins a substantial body of post-VHS craze films that narrativize the inherent spookiness of the tape as a tactile, physical container for the ghosts of our pasts. Even during the zenith of VHS’s circulation, unease about the storage capabilities of these encased memories became apparent within narrative cinema. What started with supernatural snuff films like Videodrome (1983) and Benny’s Video (1992) swelled into a subgenre that persists beyond the medium’s heyday. Cursed videotape fare, a trend initiated by Ringu (1998) and its 2002 American remake, render horrific the process by which videos are made. For instance, in both Ringu and The Ring, a murdered child exacts her revenge by creating a cursed videotape that kills anyone who views it within seven days. Sadako’s/Samara’s projected thermography provides a supernatural sheen to the quotidian process of home recording. Both films follow a detective arc, wherein a cursed viewer is tasked with uncovering the tape’s origins. This question, “Who made the film,” provokes a second, more ominous question: “Why would you film it?” Ethan Hawke as crime writer Ellison Oswalt in Sinister (2012) asks precisely this question when he discovers a box with a projector and Super 8 reels bearing innocuous home movie titles like “Family Hanging Out” and “Barbecue” that instead depict brutal family annihilations by a demon who lives within the images.

But why does anyone film anything? To remember it and, in the case of home viewing, to watch it repeatedly, allowing the images to spread across time like a curse. It is not so much the contents of the VHS itself that imbues the object with ill will—although the images certainly disturb—but the desires that become entangled with those images through the process of mediation: the nefarious motivation to record upsetting acts, the ignorant anticipation of the unsuspecting viewer, and the melancholic thrust back into a time and place where you no longer belong. Both The Ring and Sinister feature extensive montage sequences of video copying and editing which are enabled through home viewing means. Close-up shots of hands using the technology that lets them fiddle with the recordings emphasizes how the viewer can alter how they see the images—and, in the case of The Ring, literally alters what the images are. These sequences synthesize a fantasy of control over home recording technologies, which, by the very nature of the memories that these technologies capture, allows the editor to rewrite the ghosts of their former self.

Underlying panic that illicit and/or demonic acts could be safeguarded within a tape’s casing, only to be reanimated later onscreen, has only grown as the medium becomes increasingly inaccessible. While films that critique the relationship of the image to reality span decades and genres, the specific subject of the VHS as a corrosive object that occludes a past now in need of conjuring remains firmly within horror’s purview. These films sense how the millennial nostalgia for the VHS is tinged with the supernatural, a paradoxical longing for the contents of Pandora’s box whose opening could unleash all manner of demons. Recently, cravings for the millennial nostalgia of the VHS has prompted attempts to put the demons back in the box in order to provoke renewed awakenings, like with the 2024 release of Alien: Romulus on a “fully functioning” VHS and A24’s VHS trifecta of Schoenbrun’s film, Kyle Mooney’s Y2K (2024), and Gaspar Noé’s Climax (2018). These releases stirred controversy among the VHS collector community who maintain VHS as a format best reserved for films released during the technology’s heyday, as if the vessel itself dictates the types of ghosts they can entrap. Fortunately for any unsuspecting VHS viewer, the challenge of obtaining a functioning VCR ensures that the demons will remain trapped. The cursed technology subgenre seems to have skipped over the DVD entirely, as screenlife films like Unfriended (2018) and Host (2020) trade the VHS for the internet as our ghosts’ new dwelling.

Whether home recording risks the viewer getting sucked in Schoenbrun-style or releasing something out á la Ringu and Sinister, VHS opened a portal between worlds, between past and present, so both could exist in the same room. VHS hypnotized us into believing this portal would remain open. The physicality of the VHS creates the illusion that we can not only contain the past but hold in our possession a durable, tangible mechanism that is continuously accessible. And yet, this magical circumvention of the physics of time now requires an expanding annex of mystical processes in order to work; as our memories and our technologies become increasingly unreliable or unplayable, and we only feel more strongly compelled to conjure them. The VHS formats the past as a ghost in a haunted house, a spirit trapped in an earthly vessel. We know it’s there because we can hold it in our hands, but we cannot see what is inside. A midnight realm indeed.

Emily Naser-Hall is an assistant professor at Western Carolina University whose research focuses on cultural narratives of privacy, sexuality, and memory in very good and very, very bad movies. She spent every October weekend of her high school career working at a haunted house, so now the only things that scare her are clowns and running out of coffee.

Article thumbnail from via Wikimedia